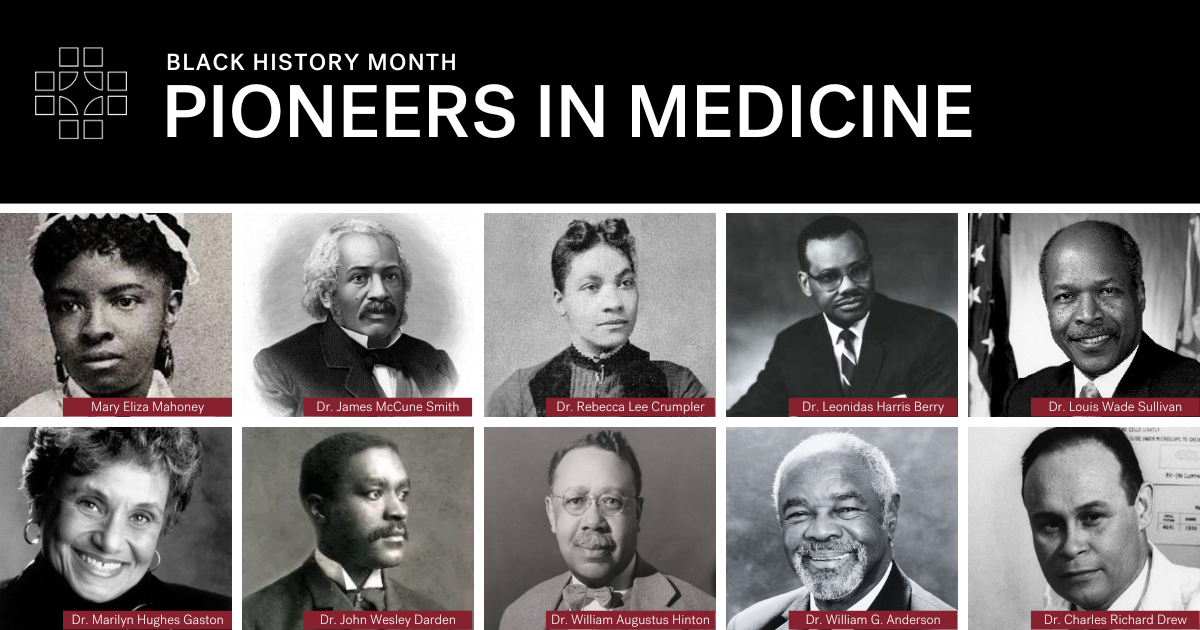

Celebrating Black History Month at EAH

In celebration of Black History Month, we are recognizing trailblazing African Americans who broke barriers, overcame discrimination, and paved the way for health equity in the United States.

Mary Eliza Mahoney (1845 – 1926)

Mary Eliza Mahoney was the first Black person to graduate from an American school of nursing in 1879. She went on to become the first professionally trained Black nurse in the United States.

Dr. James McCune Smith (1813 – 1865)

Dr. James McCune Smith was the first African American to earn a medical degree, earning his degree at the University of Glasgow in Scotland. Upon returning to the United States, he became the first Black person in the nation to run a pharmacy.

Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler (1831 – 1895)

In 1864, Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler became the first Black woman to earn a medical degree in the United States. She first practiced medicine in Boston and primarily cared for poor African American women and children.

At the end of the Civil War in 1865, she moved to Richmond, Virginia to provide missionary service, as well as to gain more experience learning about diseases that affected women and children. Despite experiencing intense racism and sexism from her male colleagues, Dr. Crumpler became a successful physician and medical author. Today, her home on Joy Street in Boston is a stop on the Boston Women’s Heritage Trail, and in 2021, February 8th was declared “Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler Day” in Boston in celebration of what would have been her 190th birthday.

Dr. Leonidas Harris Berry (1902 – 1995)

In 1946, Dr. Leonidas Harris Berry became the first black doctor on staff at the Michael Reese Hospital in Chicago, Illinois, but even as a renowned gastroenterologist, he had to fight for an attending position there. In the 1950s, Berry chaired a Chicago commission that worked to make hospitals more inclusive for Black physicians and to increase facilities in underserved parts of the city.

His dedication to equity for Black Americans reached beyond the clinical setting, as he was active in a civil rights group called the United Front that provided protection, monetary support, and other assistance to Black residents of Cairo, Illinois, who had been victims of racist attacks.

Dr. Berry was finally named to the attending staff of Michael Reese Hospital in 1963 and remained a senior attending physician for the rest of his medical career.

Dr. Louis Wade Sullivan (1933 - )

Dr. Louis Wade Sullivan was the founding dean of what became the Morehouse School of Medicine, the first predominantly Black medical school opened in the United States in the 20th century. Later, Dr. Sullivan served as secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, where he directed the creation of the Office of Minority Programs in the National Institutes of Health’s Office of the Director.

Dr. Marilyn Hughes Gaston (1939 - )

Dr. Marilyn Hughes Gaston was a leading researcher on sickle cell disease and deputy branch chief of the Sickle Cell Disease Branch at the National Institutes of Health. Her groundbreaking 1986 study led to a national sickle cell disease screening program for newborns. Her research showed both the benefits of screening for sickle cell disease at birth and the effectiveness of penicillin to prevent infection from sepsis, which can be deadly for those with sickle cell disease.

In 1990, Dr. Gaston became the first Black female physician to be appointed director of the Health Resources and Services Administration’s Bureau of Primary Health Care. She was also the second Black woman to serve as assistant surgeon general as well as achieve the rank of rear admiral in the U.S. Public Health Service. Dr. Gaston has been honored with every award that the Public Health Service bestows.

Dr. John Wesley Darden (1876 – 1949)

Dr. John Wesley Darden was the first Black physician in the Auburn/Opelika area after moving to the area in 1903. At the time, he was the only Black physician for a 30-mile radius, and he began working 18-hour days to serve the Black community in Lee County. Today, Dr. Darden’s house in Opelika is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and houses the J.W. Darden Wellness Center which offers health screenings and education to people in the community

William Augustus Hinton (1883 – 1959)

Despite earning a medical degree, with honors, from Harvard Medical School in 1912, racial prejudice prevented Dr. William Augustus Hinton from pursuing a career in surgery at any Boston-area hospital. Instead, Dr. Hinton volunteered as an assistant in the Department of Pathology at Massachusetts General Hospital, performing autopsies on people suspected of having syphilis. He became an expert on the disease and created a new blood test for diagnosing syphilis that was adopted by the U.S. Public Health Service. After years of teaching preventive medicine, hygiene, bacteriology, and immunology, Dr. Hinton became the first African American to be promoted to the rank of professor at Harvard.

Dr. William G. Anderson (1927 - )

Dr. William G. Anderson attended the Des Moines University College of Osteopathic Medicine. After graduation, he returned to his home state of Georgia, where he founded and led the Albany Civil Rights Movement, working closely with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Rosa Parks, and other civil rights leaders to advance the health and well-being of Black communities. In 1964, he became the first Black surgical resident in Detroit’s history and, in 1994, he became the first Black president of the American Osteopathic Association

Dr. Charles Richard Drew (1904 – 1950)

Known as the “father of blood banking,” Dr. Charles Richard Drew pioneered blood preservation techniques that led to thousands of lifesaving blood donations. Dr. Drew’s doctoral research explored best practices for banking and transfusions, and its insights helped him establish the first large-scale blood banks. Dr. Drew led the first American Red Cross Blood Bank and created mobile blood donation stations that are now known as bloodmobiles.

Despite his renown for blood preservation, Drew’s true passion was surgery. He was appointed chairman of the department of surgery and chief of surgery at Freedmen’s Hospital in Washington, D.C. (now known as Howard University Hospital). During his time there, he went to great lengths to support young African Americans pursuing careers in medicine.